What Is an Investment?

This post will explain the differences between bonds vs stocks vs mutual funds vs exchange-traded funds, but before we do that, we have to define “an investment.” At the most basic level, an investment represents foregoing current consumption in order to buy something in the future. In other words, instead of buying one banana today, I set aside my money so I can buy two bananas in the future. Why would I do that? Maybe I have more bananas than I need today. Or maybe I just really want to be able to buy multiple bananas in the future.

Expected Return

To determine the rate that I require for my investment, there has to be some sort of compensation for foregoing present consumption. That compensation is an expected rate of return. If I’m going to invest my money for the future, and there’s a lot of certainty around when I’m going to get it back and how much I’m going to get it back, I don’t need that much compensation. On the other hand, if I’m not sure I’m ever going to see my money again, or I don’t know what sort of rate of return I’m going to get, I want more compensation for investing. And that leads us to stocks and bonds.

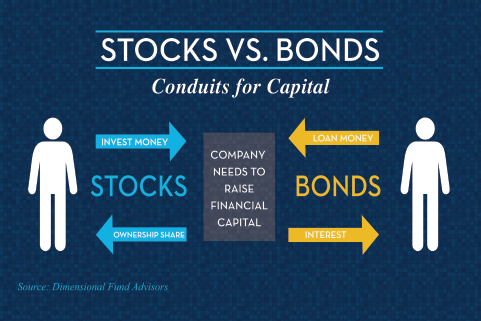

What Is a Stock?

With a stock, there is a great deal of uncertainty around the future return of stocks. It’s not a contractual obligation, it’s an ownership share. When I buy a stock, they don’t have a legal contract saying they need to pay me a certain rate. There are dividends, but if they are not paid, then little to nothing happens on the corporate side. Maybe the stock price even falls. If I’m going to buy a stock, I’m going to demand a higher rate of return than a bond. The more volatile the stock, maybe the lower the dividends it pays, the less proven its business model, and the higher my required rate of return.

An investment is a future consumption in exchange for current consumption – with a required rate of return. Stocks are generally riskier and more aggressive than bonds, but with higher required rates of return. Which leads us to own stocks and bonds in my portfolio.

What Is a Bond?

A bond is a contractual obligation with an issuer that requires them to pay me, otherwise, they are legally in default. If I’m buying a government bond, I’m lending money to the federal government. If they don’t pay me back, they’re technically in default. It is the same situation with a company: I lend money to a company, they’re contractually obligated to pay me back. That’s a corporate bond. The less creditworthy the company, the higher the rate of return I will require. This is because they are less likely to pay me back or in other words, I have less confidence that they will have the ability to pay me back. Similarly, the longer I’m investing my money, the more return I want. If I’m lending my money overnight, I don’t need a high return. If I’m lending it for 30 years, I want a higher return, because who knows? A lot can happen during that period.

Why Would I Buy Bonds?

When I buy bonds, I’m buying bonds for three reasons:

- Income

- Diversification

- Safety

Income: Income from bonds comes in the form of a coupon. Bonds pay, generally, semi-annual interest. Then at maturity, I get my principal back. That’s a valuable function, especially when I’m attempting to generate a paycheck from my portfolio.

Diversification: More often than not, bonds move in the opposite direction of stocks. If stocks are going up, bonds may not perform as well. When stocks fall, or when they’re in a bear market, bonds tend to do OK. That’s not always the case. As it turns out, in periods where inflation is above 3%, stocks and bonds tend to move in the same direction. This is called correlation when the similarity between the returns of stocks and bonds is growing and moving towards 1.0, or moving in the same direction, as inflation rises. In other environments, there tends to be very little correlation. That’s why I like combining the two asset classes.

Safety: I mentioned that sometimes bonds fall, or they don’t do as well as stocks, but a bad year in the bond market is very different than a bad year in the stock market. In fact, the worst year for bonds in the last three decades was 1994, when the bond market, as measured by major indexes, fell about 3 percent.1 3% is a bad day in the stock market, but it’s the worst year in many decades in bonds. This illustrates how bonds tend to be a much safer asset class than stocks. Because of that safety and diversification, you don’t want to be overly aggressive in seeking income from your bonds. You want income, sure, but remember: bonds should also satisfy those other two functions of income and diversification. High yield bonds, emerging market bonds, preferred securities, bank loans, other riskier types of bonds may provide more income, but they may not fulfill the important considerations of diversification and safety you’re looking for when you decide to buy bonds. Short to intermediate maturity (say, 10 years and under), high quality, investment-grade rated bonds can fulfill all three functions of income, diversification, and safety.

Should you invest in bonds? Check out this blog post to help you decide.

Why Would I Buy Stocks?

When you decide to buy stocks, it’s because you’re looking for growth. This is where you need your portfolio to grow at a certain rate of return over time in order to meet your financial goals. This is where inflation comes into play over time, and you need asset classes that are going to keep pace with, or maybe even exceed inflation – and that’s what stocks do. Company dividends can grow. A good company may increase their dividend over time. You may see capital appreciation if the company’s profits, growth prospects, or dividends increase. The idea of buying stocks is that, by adding them to a portfolio, you have higher expected returns over time.

In a hypothetical example, maybe the long-term average of bonds is somewhere in the 3 to 5 percent range, depending on what kind of bonds I’m buying. The long-term average for stocks is maybe somewhere in the 6 to 10 percent range, depending on my time frame and the type of stocks. By purchasing both stocks and bonds in some mix – many people go with 60/40, 50/50, 70/30, or vice versa – I’ll wind up with a blended portfolio that returns somewhere in the 5 or 6 percent range. I’ll have much less volatility than buying only stocks, and higher returns than buying just bonds.

What Investment Vehicle Should I Use?

When it comes time to decide what kind of investment to buy, I have a choice. I’ve made the determination to buy stocks or bonds or both. Now I need to choose a vehicle. That can be individual securities, it can be mutual funds, or it can be exchange-traded funds, often called ETFs.

Stocks and Bonds Are Different Than Mutual Funds and ETFs

Individual securities are exactly what the name implies. I go out and buy an individual stock. Microsoft, General Electric, Apple, and the like. Or an individual bond, such as a municipal bond or a Treasury bond. Now the good part about that is I select exactly what I want. I know exactly what I own. Also, there are no ongoing fees or management expenses. The bad part is, I’m responsible for doing the ongoing management, research, and due diligence of that portfolio. I’m also responsible for monitoring the portfolio myself. Most people are not professional credit or securities analysts, so they’re taking on a function for which they may not have training. Depending on the size of your portfolio, it can also be difficult to get appropriate diversification with individual securities. This is why mutual funds and exchange-traded funds came into being.

Mutual Funds and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs)

Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are not investments, in the sense that a stock or a bond is. Stocks and bonds are asset classes. Mutual funds and ETFs are pooled investment vehicles, where the money of a number of investors is taken together to buy large blocks or large collections of securities.

The Pros and Cons of Mutual Funds and ETFs

Owning a mutual fund or an ETF gives you instant diversification. It also gives you professional management. Those are the positives of mutual funds or exchange-traded funds. The downside, of course, is that you get less control over what you own. Once you buy a mutual fund or an ETF, you don’t have any control or say over what goes into or out of it. It could be an active decision on the basis of a mutual fund manager that decides what goes in and out – someone who should be a trained professional credit or securities analyst. What goes into or out of the mutual fund or ETF could also be rules-based. For example, an S&P 500 fund that only buys stocks in the S&P 500. Either way, you have no say in what you own, ultimately.

There are also ongoing expenses involved with ETFs and mutual funds which need to be taken into account. That being said, with many mutual funds and ETFs in this day and age, expenses are relatively low. And if you shop around, you should be able to mitigate expenses to a reasonable degree.

There are pros and cons of course, as with anything in investing, to owning individual securities, or owning mutual funds, or owning ETFs. Ultimately, for many, many people, those pooled vehicles are going to make the most sense. Individual securities may be suitable to complement your holdings, but for many people, the foundation of their portfolio is going to be those pooled vehicles, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that focus on relatively low costs, relatively broad diversification, and a relatively consistent investment style.

In Summary

When it comes to investing, your first task is to decide, “Do I want stocks vs bonds?” For most people the answer isn’t, “I want one” or “I want the other,” it’s, “Yes, I want both,” and then choosing your combination of the two. Next, you would decide which vehicle to use to implement your asset allocation choices, whether that vehicle for your investments is mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, or individual securities.

For more information on this or any other personal finance topic, contact us at Pure Financial.

- Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, Data from 02/1976 – 01/2018.