An unusual phenomenon has been taking place in the stock market the last several years. You see, the high-flying stocks of popular “growth” companies have been outperforming those of beaten down “value stocks.”

The fact is, value stocks have historically outperformed growth stocks, both in the U.S. and abroad, and they have done so on a pretty consistent basis and by a fairly wide margin.

Before discussing this further, let’s pause for a moment, and define “growth” and “value.”

What Are Growth Stocks?

Growth stocks tend to be linked to companies with strong recent performance or exciting prospects for the future. Think of social media, driverless cars, or biotech companies. The downside of buying this expected growth comes in the form of higher stock valuations.

What Are Value Stocks?

Value stocks are the tired, old, beaten down companies, suffering from weak recent performance, negative headlines, or bleak prospects for the future. The silver lining? These difficulties result in stocks that are valued less dearly.

Why has growth been outperforming value?

You might be wondering exactly why growth has been trouncing value lately. But alas, this is the financial markets we are talking about, an arena where exactitude is often in short supply.

As such, they’ve been attracted to companies with superior growth prospects, while focusing somewhat less on the price they are paying for that growth. The result has been strong gains for growth stocks, at the expense of value stocks.

But what does the historical record tell us?

Everything in markets is cyclical. There have always been periods when value outperforms growth, and periods when growth outperforms value. Since I don’t know how long the current cycle might continue or when it might reverse course, all I can do is focus on the long-term historical track record. And that record tells me that over an 89 year period, from 1927-2016, the average annual premium U.S. value stocks produced ranged from 1.5% to 5%, depending on the indices you measure.*

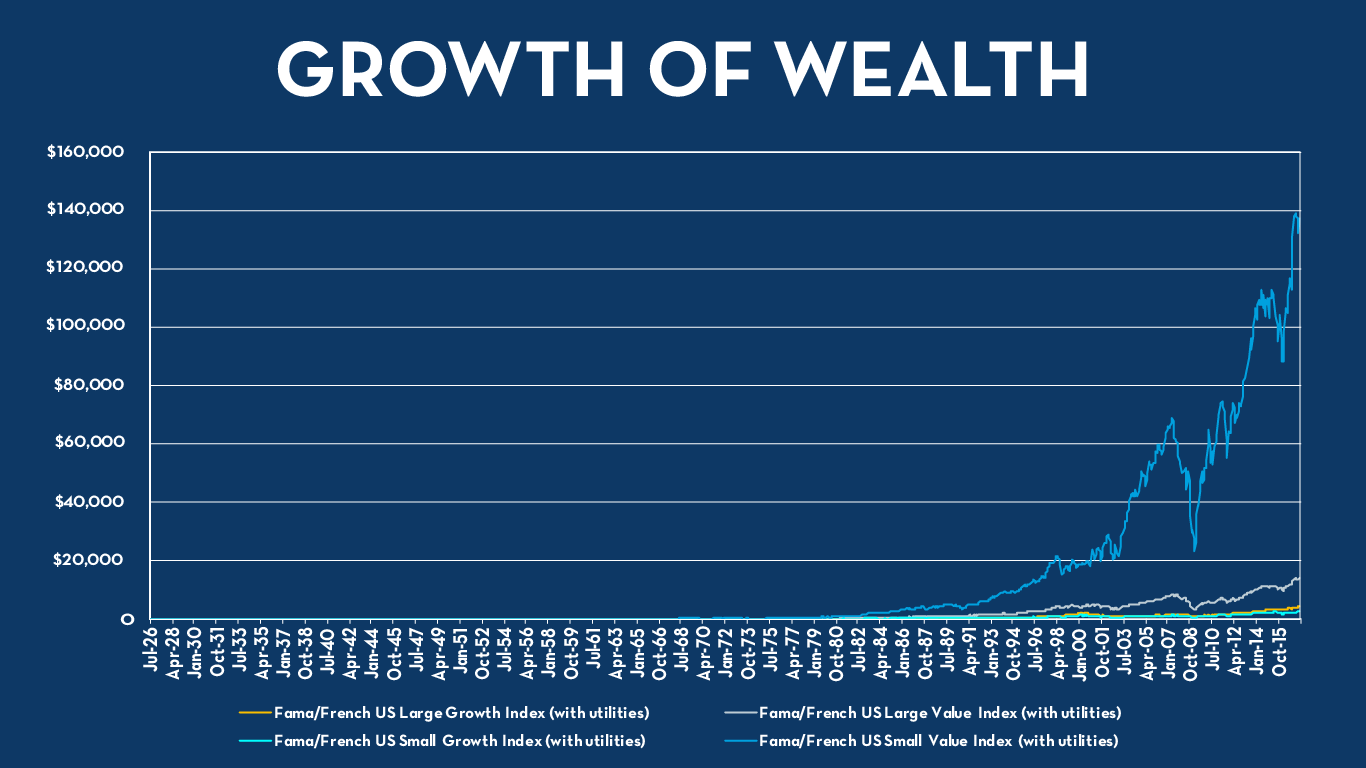

That differential was sufficient to produce the following results:

The chart above measures the cumulative returns of $1.00 invested in each of 4 different indices, starting in July 1926. The indices measure U.S. Large Cap Growth, U.S. Large Cap Value, U.S. Small Cap Growth, and U.S. Small Cap Value.

Over the course of 91 years, $1.00 invested in Large Cap and Small Cap Growth stocks would have grown to $4,301 and $2,619 respectively.

One dollar invested in Large Cap and Small Cap Value stocks would have grown into $13,937 and $137,223 respectively.

That’s right, the difference between compounding one dollar at 9.03% versus compounding at 13.88% is the difference between a pair of plane tickets from Los Angeles to London (coach!) and a new vacation condo in Cabo San Lucas.

That, my friends, is the magic of compound interest – played out across decades.

This is the very reason why my colleagues and I focus so diligently on “the little things” like fee and tax minimization or eking out a bit more return in a portfolio.

How persistent is the value advantage?

Ok, so value stocks have historically crushed growth stocks. But earlier I mentioned that growth has recently been in ascendancy, so you might be wondering what the odds are that value recovers.

Well, my crystal ball is a little murky, but let’s look at the historical record.

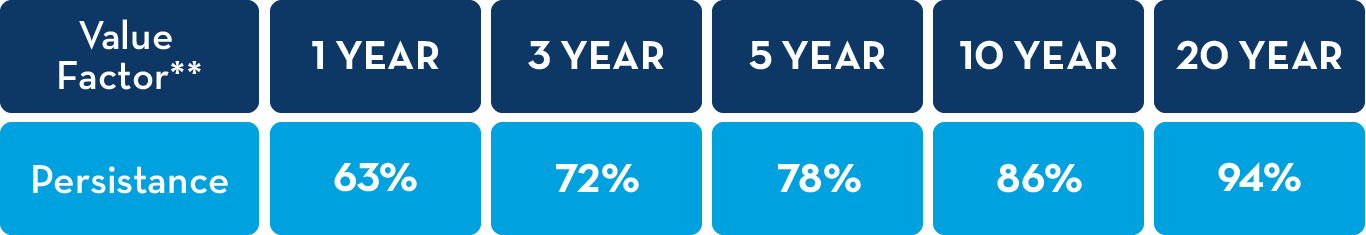

The chart above measures how persistently value has outperformed growth from 1927 – 2015. In other words, value has outperformed growth in 63% of the years (or 55 out the 88 years). Similarly, value has won out over growth in 78% of the 5-year time frames since 1927. And over 20-year periods, value has beaten growth 94% of the time.

Based on the data, I’d conclude that the longer someone sticks with a value-focus, the better their odds of outperforming someone taking a growth approach. Nevertheless, there have been some multi-decade periods where value has lagged growth (6% of the time.) And there is no way to tell ex-ante whether or not we are currently in the midst of what will become another long-term period where value lags growth.The chart above measures how persistently value has outperformed growth from 1927 – 2015. In other words, value has outperformed growth in 63% of the years (or 55 out of 88 years). Similarly, value has won out over growth in 78% of the 5-year time frames since 1927. And over 20-year periods, value has beaten growth 94% of the time.

So does a focus on value make sense?

The value advantage may or may not continue in the future, and even if it does continue it is impossible to know whether the scale of the outperformance will remain similar to its historical average. However, I do believe that in this case, the past is likely to be a prologue to the future, and the reason is that the outperformance of value stocks makes sense from both an economic and behavioral perspective.

From an economic perspective, value stocks generally represent companies with either an inferior track record or less robust future prospects than growth companies. As such their cost of capital has to be higher. Think of it like this – if two borrowers walk into the bank to get a mortgage, the borrower with a 780 FICO score is going to get a much better rate than the one with a 620 FICO because the bank requires a higher return to “invest” in the riskier borrower. The same principle holds true for companies – if value stocks didn’t offer higher potential returns, investors would never look in their direction.

Additionally, value stocks have been more volatile over time, as measured by standard deviation. This means that from a portfolio construction perspective, value stocks should offer commensurately higher absolute returns in order for investors to consider them on a risk-adjusted basis.

Finally, there are behavioral biases that lead value stocks to offer higher prospective returns than growth stocks. That is because investors, as a whole, have a preference for growth stocks. There are multiple reasons for this, but two of them include: investors feel more comfortable buying companies they are familiar with and which they and their neighbors use on a daily basis (think of Netflix or Amazon.) The inverse of this is that investors are less comfortable buying unfamiliar companies, or even worse, companies making headlines for the wrong reasons. As such, there is less demand, which leads to less expensive valuations, which leads to higher long-term returns.

- Investors feel more comfortable buying companies they are familiar with and which they and their neighbors use on a daily basis (think of Netflix or Amazon.) The inverse of this is that investors are less comfortable buying unfamiliar companies, or even worse, companies making headlines for the wrong reasons. As such, there is less demand, which leads to less expensive valuations, which leads to higher long-term returns.

- There is a “lottery ticket” effect in growth stocks that is not present in value stocks. Basically, this means that investors like buying something where the perceived downside is minimal, but the potential upside is huge. We’ve all met people that are still bragging about how they killed it on a particular IPO (and yet the track record of IPOs as a whole is abysmal.) Since this “lottery ticket” mentality isn’t present with slow growth value stocks, relative valuations and future expected returns tend to be higher.

Key Takeaways

- Value stocks have historically produced much higher returns than growth stocks

- This outperformance has ebbed and flowed but has been pretty consistent if given a reasonably long time horizon

- There seem to be sound economic and behavioral explanations for this outperformance

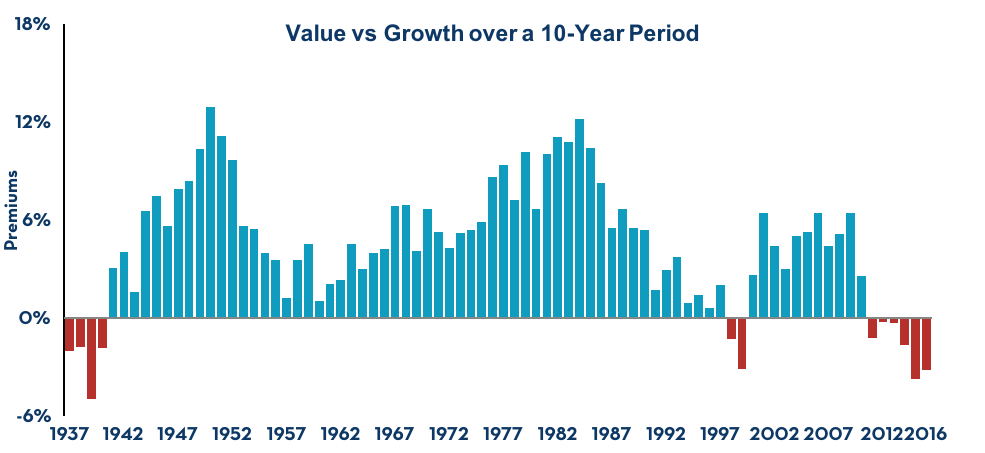

- Since 2011 though, and in an unusual twist, growth stocks have done much better than value stocks (the blue lines below reflect when value is beating growth over a 10-year period, and red lines are when growth is winning out)

- In fact, the chart below reflects that this is just about the worst stretch for value stocks since before World War 2.

Like I mentioned above, my crystal ball is broken, and I don’t know for sure what the future holds. But, if, as the old saying goes, “History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes,” then I have to think that at some point value stocks will once again have their day. The key, as always, is to have a diversified portfolio that produces reasonable returns across most market environments, while remaining positioned to excel when value once again shines brightly.

**Statistics from “Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing” by Swedroe & Berkin

Disclosures: The indices shown are for informational purposes only and are not reflective of any investment. As it is not possible to invest in the indices, the data shown does not reflect or compare features of an actual investment, such as its objectives, costs and expenses, liquidity, safety, guarantees or insurance, fluctuation of principal or return, or tax features. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Neither diversification nor asset reallocation can ensure a profit or protect against a loss. There is no guarantee that a diversified portfolio will enhance overall returns or outperform a non-diversified portfolio.

Opinions expressed are subject to change without notice and are not intended as investment advice or to predict future performance.