Let’s get this out of the way upfront: I have no idea what the stock market is going to do tomorrow, next week, or next year. I also freely acknowledge that by many measures, markets are relatively expensive. Nevertheless, here are several reasons why I think sitting on the sidelines does not make a whole lot of sense.

1. Let the odds work in your favor

If you walk into a casino to play roulette, you have roughly a 45% chance of winning. In other words, the casino loses 45 out of every 100 turns of the wheel. So, if you own a casino, and know that you’ll lose almost half the time, how much do you want people to play?

As we all know, casinos try to stay open 24/7, because even though they will often lose money, over the long haul, the odds are in their favor. The same principle applies to the stock market.

Historically, stocks have produced positive premiums on approximately 55% of trading days1 (stocks have done poorly nearly ½ the time). However, just like roulette is a great long-run proposition for the casino, the stock market odds ultimately favor the investor. The more days you’re invested, the greater the chances that those positive stock market factors will work in your favor.

2. Perfect participation produces superior performance

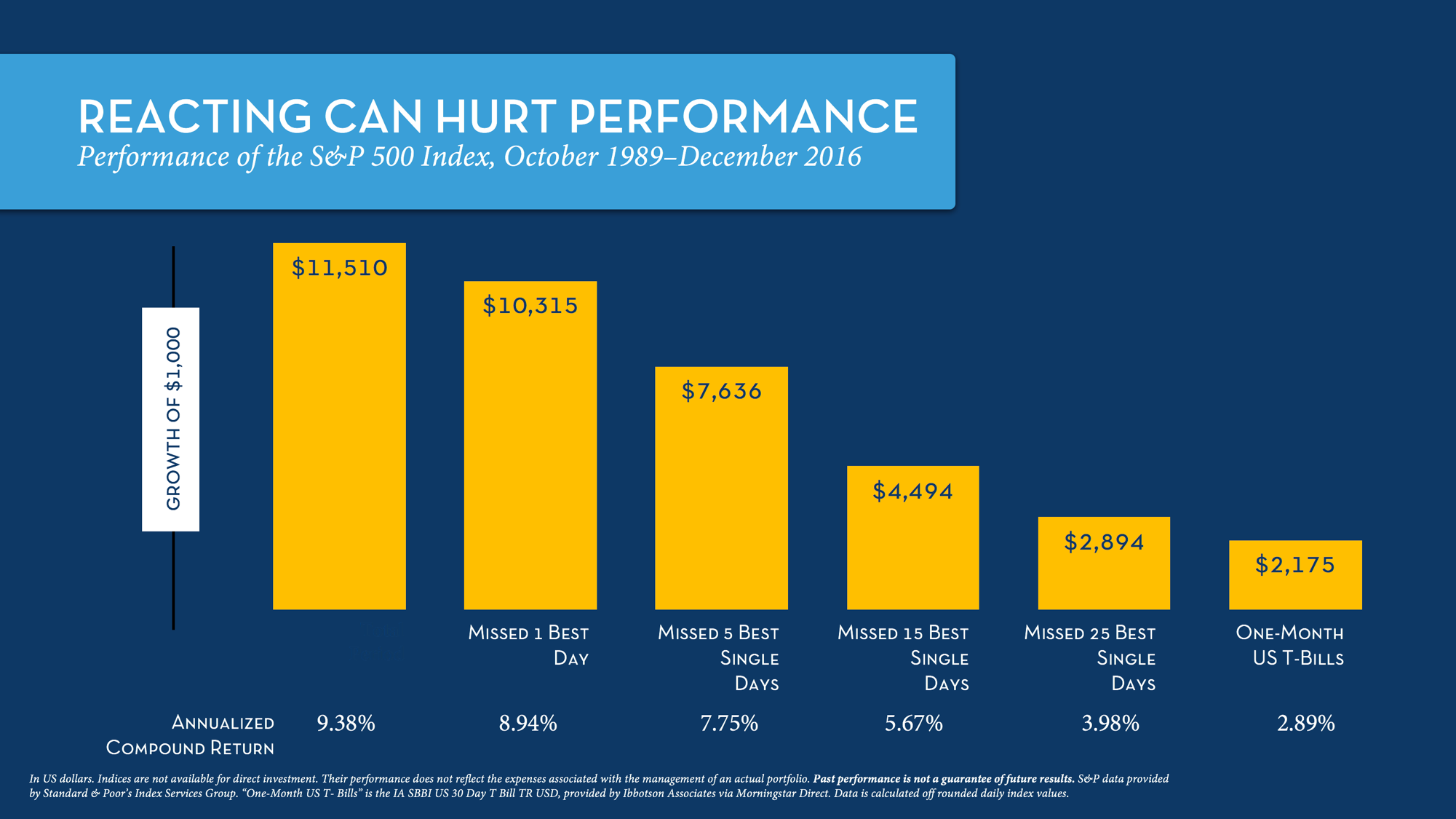

Between 1989 and 2016, there were approximately 6800 trading days in the U.S. stock market, and the S&P 500 produced a compounded annual return of 9.38% (source).

However, investors that missed the twenty-five best trading days over those twenty-seven years (an average of missing just one day per year) saw their annualized returns fall to 3.98%.

That’s right, the difference between participating 100% of the time and participating 99.6% of the time was nearly 5.50% per year.

Let’s look at what that means in terms of dollars and cents for each situation.

Emily invested $100,000 in 1989 and stayed in the market 100% of the time and wound up with $1,125,443. She received the S&P 500* return of 9.38%.

By contrast, David invested the same $100,000 in 1989 and experienced the same markets, but he let his emotions get the best of him and missed the 25 best trading days during that time frame and wound up with only $286,843. He received the S&P 500* return of 3.98%.

Same markets, same economy, same return for the S&P, but Emily participated 100% of the time, whereas David participated 99.6% of the time. The difference turned out to be over $800,000.

Now undoubtedly, you probably wouldn’t have the misfortune to precisely miss the 25 best trading days of the past 2 ½ decades. But the basic principle remains the same; the majority of stock returns are concentrated in a small proportion of trading sessions. It is important to note that many of those days tend to occur during bear markets and periods of turmoil – exactly when the average “market timer” is least likely to be invested.

* Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. S&P data provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group.

What outcome would you prefer?

Still not convinced? Let’s put the results of 100% participation and 99.6% participation into context. According to Zillow2, the median list price per square foot for a home in the United States is $139. Using that figure, David, who participated 99.6% of the time, could liquidate his portfolio and buy a 2063-square foot home.

By way of comparison, Emily, who participated 100% of the time, invested the same $100,000 at the same time, in the same markets, could liquidate her portfolio and purchase an 8096-square foot mansion.

Both homes in the pictures above are nice, but if you invested the same amount of money and took the same amount of risk, what outcome would you prefer?

3. Inertia takes over

I still remember my first middle school dance. I showed up at the gymnasium, found my friends, and planted myself next to them, our backs firmly against the wall. Then I looked across the floor at the girls, trying to muster up the courage to ask one of them to dance. But I didn’t move right away, promising myself that I’d walk across that huge, gaping chasm as soon as the next song began. But the next song wasn’t the right one, and so, I waited. And that was followed by a slow tune – no way could I ask someone to dance to that! And before you know it, I’d waited so long that inertia took over, and I remained glued to the wall for the rest of that awkward evening.

So why am I reliving my middle school nightmares? Because sitting on the market sidelines could turn out a lot like that grade school dance. The longer you wait, the more difficult it is to get back in the game.

Think about it. When you move into cash, there are two possible outcomes going forward. One is that stock values continue to soar, and if you were hesitant to invest at a certain level, how likely are you to get back in at prices that are 10%, 20%, 50% higher?

The other possibility is that prices fall. On the surface, this is just what you are hoping for, and maybe you’ll take advantage and invest at bargain prices. But you need to be completely honest with yourself here because most people have great difficulty investing when markets are falling, the news is grim, and prices are expected to fall even further.

The result for many investors is that they wind up just like that grade-school kid, stuck on the sidelines, watching everyone else having fun.

Even Alan* can’t time markets

One final argument for why sitting on the sidelines does not make sense is: even if stocks enter a bear market, they might not return to today’s levels. For instance, what if it takes another two or three years before that downturn begins? And what if stocks spend the next couple years churning ahead at a 15% annual clip? In that scenario, the eventual downturn might still leave prices higher than they are today.

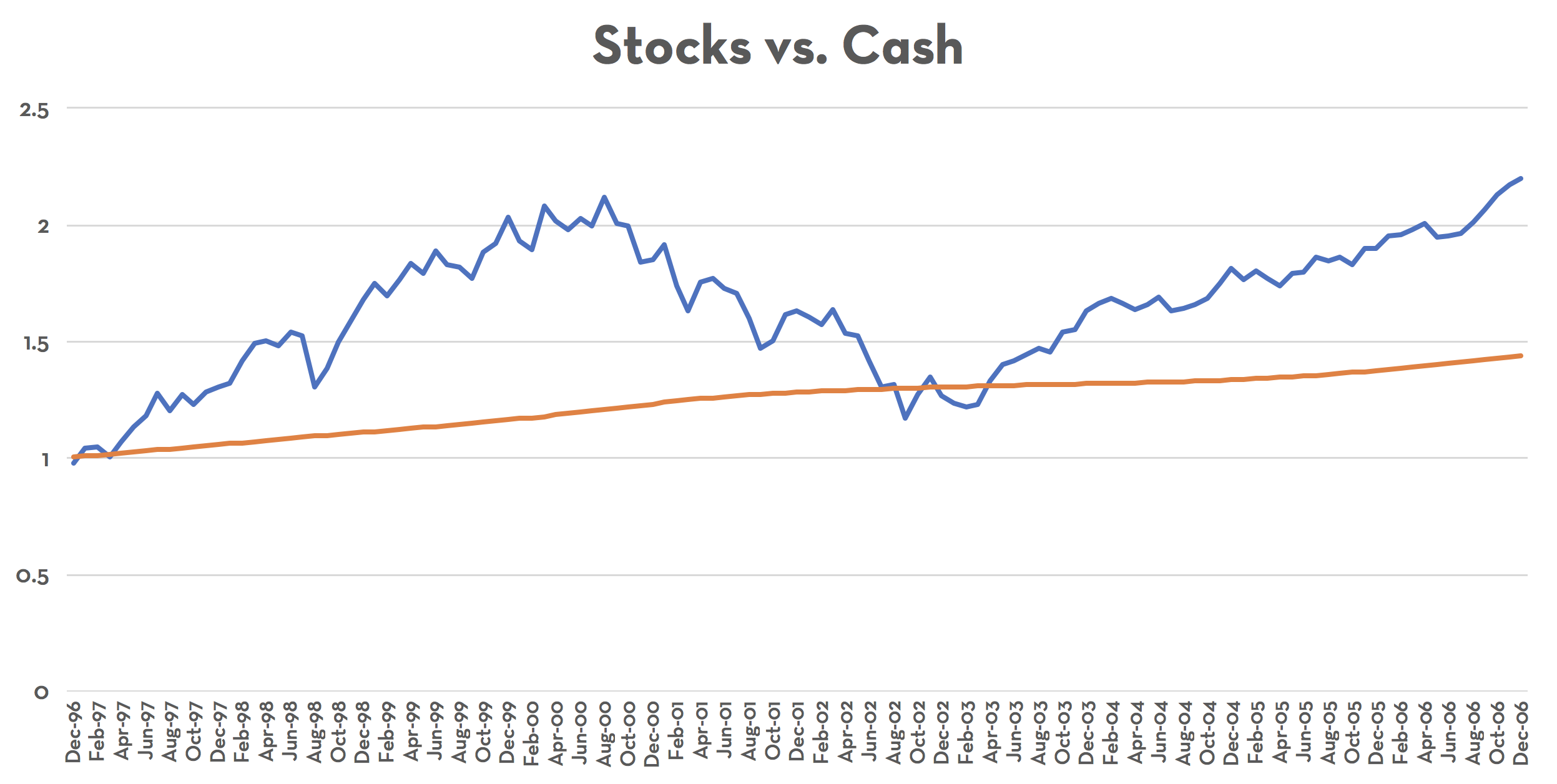

The chart above shows a real-world example of this occurring during the 10-year period from December 1996 through December 2006. The line in blue is the S&P 500 and the red line represents 3-month T-Bills. I chose those dates because in December 1996, during the height of the dotcom bubble, our friend Alan told people that markets were experiencing “irrational exuberance.” Surely, that must have been a great sign that stock prices were too high, and the time to move to the sidelines was fast approaching.

In fact, Alan was right. Stock prices were high, and a nasty correction eventually ensued.

But alas, Alan’s timing was somewhat less than perfect, and stocks continued higher for three more years before suffering a sharp reversal. And so, despite a horrendous stock market correction, investors that stayed the course drastically outperformed those that moved to cash following Alan’s warning.

And yes, there was a brief period around 2002 where someone could have bought stocks ever so slightly more cheaply than they could have in 1996 – that’s the small window where the blue line drops below the red.

But this is the exception that proves the rule: Yes, timing in and out of the market can be done, provided someone has a crystal ball and can precisely forecast the future. But if Alan didn’t have perfect timing as to when to get out of the market, why should we expect him to have perfect timing as to when to get back in?

*For those that haven’t guessed yet, our friend “Alan” is Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987-2006. And if the Chairman of the most powerful Central Bank in the world can’t successfully predict markets, even though he sets the rules that help move those markets, how good are the odds for the average investor?

Conclusion

So, here’s the bottom line:

- Moving in and out of stocks or sitting on the sidelines is a viable investment strategy, provided the investor has perfect timing and can precisely predict both when markets will fall and when they are prepared to rebound

- For less omniscient market participants, staying the course and taking advantage of the long-run upward movement of stock markets is a vastly preferable course of action