Designing a portfolio that meets your needs can be a challenge. Not only do you need to select investments to meet your return objectives, but also manage how much risk you take. Also, you need to actually implement those decisions, select the most appropriate products or individual securities in accordance with your asset allocation, and purchase them in the most efficient way possible.

At this point, it can be tempting to sit back and ignore your portfolio, but in reality – the work has just begun. To ensure your portfolio still meets your objectives, you can use these best practices for portfolio rebalancing.

Portfolio Rebalancing Strategies & Best Practices

Rebalancing your portfolio is important because your investments will change in value over time and the initial percentages you chose for various asset classes will deviate. Investors who wish for a simple 50/50 stock/bond mix find that this allocation doesn’t remain intact for long. For example, the appreciation of equities at a greater rate may lead to an allocation that is 55/45 or even farther away from the initial allocation. When this occurs, it is necessary to rebalance your portfolio back to your initial allocation.

Let’s assume your initial allocation remains static and will not be adjusted over time. (We’ll discuss this possibility later.) In this case, as certain assets rise and fall it will be imperative to adjust in a few ways. You will need to understand your overall rebalancing strategy then examine different ways to implement your rebalancing plans from a practical standpoint. Let’s look at a couple different rules of thumb that are common ways to determine when to rebalance.

Periodic Rebalancing

Periodic rebalancing is a very common strategy. This means that you will rebalance at a certain frequency; perhaps annually or once per quarter. Rebalancing too frequently can be difficult to manage in addition to possibly creating excessive transaction costs and tax implications. Since it is entirely possible for a portfolio to require rebalancing before a planned point in time, many use another strategy of boundaries and ranges in addition to rebalancing periodically, rather than increasing the automatic frequency at which rebalancing occurs.

Range Rebalancing

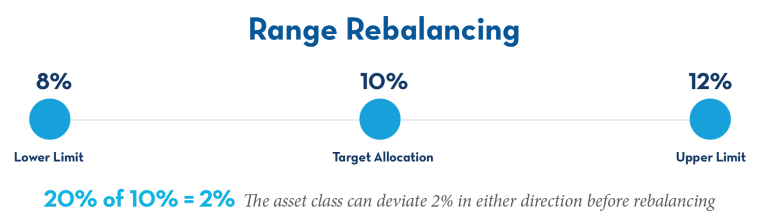

Using a range within which an allocation can deviate is a good method to control the maximum amount a portfolio can be out of balance before acting. Assume that an asset class was supposed to represent 10% of the overall portfolio, and your deviation range is 20%. In this example, you would rebalance that asset class once it deviates below 8% or greater than 12%.

Perhaps this is our allocation to small cap equities. If small-cap equities are doing quite well (or at least quite well relative to the other asset classes we hold) it’s entirely possible that the percentage could exceed our 12% threshold. We could at that point sell to return our allocation to 10%.

The specific ranges that are effective are debatable and can depend on the number of asset classes held in the portfolio as well as overall balance and risk tolerance. Choose a range that is narrow enough to ensure the portfolio still resembles your desired allocation but wide enough that it does not likely result in excessive transactions.

What to Do When it’s Time to Rebalance

Portfolio Rebalancing Strategy #1

When it’s time to rebalance, there are a few ways to go about doing so. One method is to sell assets that have deviated beyond their desired percentage and using the proceeds to purchase more of the assets that have fallen below the desired percentage allocation. This method provides a lot of flexibility although it is not without disadvantages. The substantial number of transactions can lead to potentially higher transaction costs in all account types. In non-qualified accounts, there may also be tax implications.

Portfolio Rebalancing Strategy #2

When possible, it can be advantageous to rebalance using a known event such as a withdrawal or distribution from an account. If you are contributing to the account, simply arrange your purchase of specific assets such that they are back to your desired allocations. If withdrawing, raise the cash by selling more of assets that have appreciated and less of those that have not. This strategy will give you a better likelihood of reaching your desired allocation than simply buying or selling evenly among all assets or in the same percentage as your desired allocation.

Portfolio Rebalancing Strategy #3

Along similar lines, if you are taking regular income from the portfolio, it’s important to understand that it does not necessarily need to come from those assets that naturally produce income in the form of interest or dividends. Your high growth but low or no yield assets may be a better source of income by selling off small portions at a time. This is a commonly applied approach referred to as creating “synthetic dividends.” It can also help to keep your portfolio in balance over time.

How to Treat Cash When Rebalancing

The treatment of cash in your portfolio is important to address in the context of rebalancing since there are many methods you can manage your cash position. Some portfolio managers, for example, do not hold a meaningful cash position at all, preferring to raise the funds to purchase assets by the sale of other items in the portfolio. Those who do not maintain a cash position doesn’t mean they believe that an investor shouldn’t have cash. Some do so because they believe an investor’s cash should be in an emergency fund easily accessible when needed, such as a bank savings account, rather than commingled with an investment portfolio. Others refrain from taking a meaningful cash position if some of the investment selections they make already do so (certain mutual funds, for example).

Those who do hold a cash position have a variety of approaches. Some will hold a cash position that they treat like any other asset class, aiming for a ballpark percentage in cash. Others see the cash in their portfolio as a tool to provide flexibility for unusual events, such as a substantial decline in a specific asset or to meet unexpected liquidity needs – much like an emergency fund outside the portfolio. If the rest of the assets held by these investors are in proportion with one another, they may either not care that the cash no longer represents their desired allocation amount, or they may wait for subsequent contributions to increase their cash rather than raising from the sale of other assets. Decide beforehand how you’d like to treat cash in your own portfolio, so you can maintain a disciplined plan.

Your Portfolio Diversification Strategy Can Change Over Time

Once you’ve developed a strategy for rebalancing over time, you may want to also consider if your desired portfolio allocation will gradually change over time as well. This consideration can affect your rebalancing strategy since you are effectively rebalancing to a moving target. Although, fortunately in most circumstances, this is not a fast-moving target, but one that gradually changes.

Even though there are different ways to structure a portfolio and several facts that go into the overall decision-making process, many portfolios are designed with either a desired level of risk tolerance or a specific withdrawal date in mind. Your specific circumstances will determine which approach is appropriate for you.

Portfolios with a Specific Level of Risk

Those who design portfolios with a specific level of risk tolerance oftentimes have larger or indefinite time frames. A high net worth investor who has adequate income from other sources may have investment objectives for their portfolio of leaving a legacy rather than utilizing the portfolio during their own life. On the institutional side of things, a university endowment is a good example of this strategy since the funds are being invested for an indefinite period.

Those designing and managing portfolios for either of these examples would likely make decisions based on the level of risk appropriate for the individual or institution rather than on a timeline in which the portfolio would begin withdrawals or be redeemed for some other purpose. Assuming the level of risk tolerance remains the same during the period the portfolio is being managed, a rebalancing strategy could simply be to get back to “home base” (the initial desired allocation).

Portfolios with a Changing Level of Risk

If the risk tolerance changes over time, the desired allocation would likely change as well, and the portfolio would be rebalanced to the new desired allocation. There are several reasons why an investor’s risk tolerance would change over time. Therefore, even if you are allocating to a level of risk tolerance rather than a target date, this will not necessarily be static indefinitely.

Those who have specific objectives for their portfolio involving timeframes for withdrawal or liquidation often manage their rebalancing strategy to a target date. Common strategies include:

- Managing toward a date of retirement

- A child’s anticipated college enrollment

Typically, a portfolio will start aggressively and gradually get more conservative as the need for funds approaches. This might mean that the investor who begins his retirement savings with a disproportionate amount of equities will end up lowering this percentage as retirement approaches in order to have a larger portion of bonds.

These changes will happen over extended periods of time and will not necessarily mean that the desired portfolio allocation will change each year, so it is still important to rebalance to your current desired allocation even if you intend to shift your portfolio needs over extended periods of time as specific milestones near.

When to “Set it and forget it”

Once you have set up your framework to meet your desired goals, it can be difficult to know how much of a “set it and forget it” approach to take. For investors who actively monitor their holdings, it can be tempting to rebalance not according to a plan that has been established but in reaction to short-term events or an emotional response to activity in the portfolio. On the other end, it seems possible to give too much emphasis on a plan or model, ignoring exceptional circumstances that may affect the portfolio. To what degree should plans be dogmatically applied as opposed to serving as a guideline for your judgement?

In general, you will benefit from following your plan in a disciplined manner rather than frequently altering your plans and rebalancing more or less frequently than desired. It can be difficult to trim the returns of winners in your portfolio to purchase more a lower performing asset class once the time comes to rebalance. A general assumption about future performance of asset classes in your portfolio is not a good reason to ignore your previously established rebalancing criteria. There are, however, times when an exception can make sense.

When to Make the Exception

When funds are held in taxable accounts, it can make sense to either alter or defer sell decisions based on the tax implications of the sale. An investor whose capital gains will be taxed at the highest rate this year may wish to defer sales of appreciated asset classes to early in the following year when there may be room to sell at a lower rate.

Carefully monitoring opportunities for tax loss harvesting throughout the year can minimize the degree to which your asset allocation decisions will be affected by tax considerations. While you should always take taxes into account, resist the urge to let your investment decisions be too heavily reliant on tax considerations.

Similarly, a change in rebalancing strategy or timing may be appropriate when the investment objectives or timeline materially change. This does not mean a change in daily sentiment such as being more optimistic or pessimistic about the market based on recent performance, but a material change in timeline or sentiment justifying a significant overall change in the portfolio.

An investor who decides to retire early may wish to allocate to a now-earlier target withdrawal date. An investor who has lost a second source of income and will now potentially need to rely on their portfolio for withdrawals may manage to a more conservative allocation. These examples are about reallocating the portfolio rather than rebalancing, although less extreme examples could be relevant to rebalancing strategies. If your decisions are based on changes in circumstance and information rather than emotional reactions, you have a good chance of making positive decisions.

Wrapping Up

Some of you will enjoy monitoring your own portfolio over time. Others may find the process complex and wonder how specific decisions will impact other aspects of their financial plan such as taxes or estate planning. If you’d like assistance with your overall financial planning goals, including portfolio design and rebalancing, consider a consultation with a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional.

Disclosures

Intended for educational purposes only and are not intended as individualized advice or a guarantee that you will achieve a desired result. Before implementing any strategies discussed you should consult your tax and financial advisors.

Investing involves risk including the potential loss of principal. No investment strategy can guarantee a profit or protect against loss in periods of declining values.