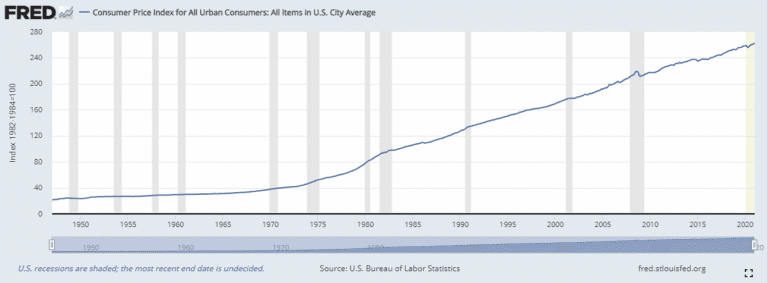

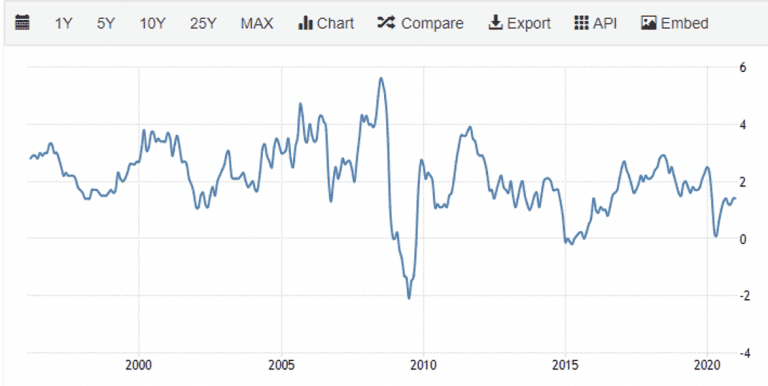

In some ways inflation is like the boogeyman – often feared but seldom seen. Over time things tend to get more expensive, but the rate of increase has generally been modest. So, while the cost of living in the United States has expanded approximately 13-fold since the end of World War 2, in the last two and a half decades, the annual rate of increase has seldom been above 4%.

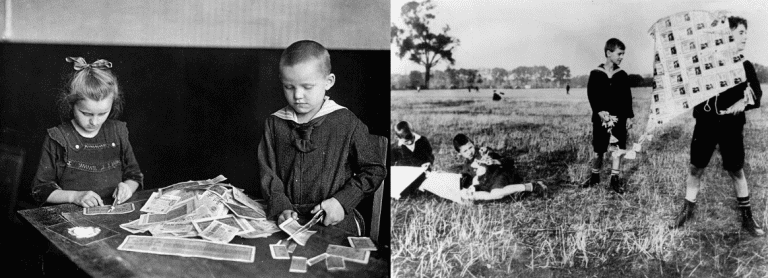

However, many people remember the Unites States’ brush with hyperinflation in the 1970s, when price increases ran at double-digit levels. Elsewhere, soaring prices have led to such ludicrous scenarios as children in Weimer Germany using currency for arts and crafts projects or to make a kite.

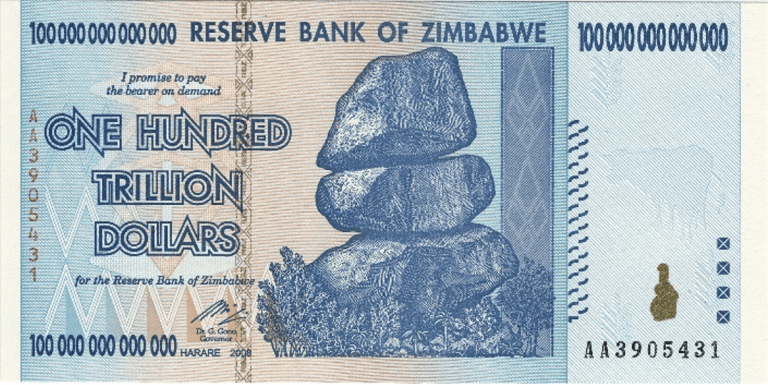

More recently, Zimbabwe’s inflation rate spiraled so high that the country took to printing one hundred trillion-dollar notes!

Today, people are worried that the impact of government stimulus and easy monetary policy will spur inflation once COVID-19 vaccinations allow the economy to reopen. Additionally, trade disagreements and a desire to move supply chains back home could undo some of the disinflationary benefits globalization and offshoring have produced.

These are all valid concerns, but at the same time, it’s important to consider that there are also some anti-inflationary factors at work. For starters, many people and businesses have seen their balance sheets weakened by the COVID-induced recession and might be slow to spend even when the economy opens back up. Furthermore, price competition brought about by internet transparency remains extremely deflationary.

Finally, the composition of the economy is different than it was back in the 1970s. At that time, America was heavily dependent on imported oil, and thus susceptible to price shocks from foreign sources. Subsequent domestic oil and natural gas discoveries mean that the U.S. is much more insulated from foreign energy markets. And employment contracts with escalating wage increases linked to the consumer price index (CPI) are much less common today, and therefore much less likely to have a snowball effect on inflation.

How would inflation impact stocks and bonds?

Hyperinflation can be devastating to financial markets, but given the historical experiences, it is extremely unlikely that policymakers would allow such a scenario to play out. In fact, even 1970s-style double-digit inflation is probably unlikely. However, that is not to say that inflation can’t increase significantly from today’s sub-2% levels, perhaps even into the mid-single digits.* If inflation were to increase to say 5%, what impact would that have on stocks and bonds?

Well, in the short run inflation surprises are generally a negative for most asset classes, but as the time horizon stretches out, stocks can be a good hedge against inflation. Many companies have a measure of pricing power and can maintain their profit margins over time, and some industries might even benefit from higher inflation. For instance, natural resources stocks tend to do well when inflation creeps higher. And the financial industry sometimes benefits from the higher interest rates which tend to accompany higher inflation.

Speaking of those interest rates, bondholders can suffer from inflation, because the future cash flows they have been promised will be repaid in less valuable dollars. The longer the time until the holder receives those cash flows, the greater the impact on the bond’s value. That is one of the reasons that we often recommend bonds with relatively short maturities, which roll over more quickly and therefore see their cash flow streams move higher in a rising interest rate environment.

What if the dollar weakens?

Another concern is the impact inflation could have on the dollar. After all, if a currency is becoming less valuable, it should depreciate against its peers. And in practice, this is often the case. One way to mitigate this impact is to hold global securities. As a U.S.-based investor, the value of your foreign holdings increases if the dollar declines. Because of that, global diversification can provide a hedge against higher inflation.

Of course, if the dollar is weakening, the question of whether to consider alternatives comes to mind. In addition to foreign currencies, common dollar substitutes include gold, bitcoin, and hard assets. When considering whether to invest in these or similar assets, it is important to understand that they do not have cash flows. When valuing stocks, bonds, and real estate, an investor discounts expected cash flows back to net present value.

If an asset doesn’t have cash flows to discount, you need to anticipate how other market participants will value it in the future. This is a fundamentally different exercise than valuing a stock or bond and relies much more on your perception of market sentiment now and in the future.

While gold has posted solid returns in the last couple of years, its price is essentially unchanged in the last decade. In fact, the last five decades have seen several major bull markets for gold, interspersed with long periods of flat performance.

By contrast, digital currencies such as Bitcoin have soared more than 100-fold in the past five years alone.

If you are considering buying Bitcoin, it’s important to be comfortable with the extreme volatility the digital currency has experienced, as well as the evolving U.S. Treasury and IRS regulations. Also consider for a moment that in the last hundred and twenty years, there have been three thousand automakers in the United States, of which less than a handful have survived. In other words, even if digital currencies are around and thriving a century from now, there is no guarantee that Bitcoin will be one of the winners.

The bottom line is that although there are some good reasons why inflation might increase, the reality is that it’s unlikely to soar anywhere near the levels some fear mongers are predicting.

What that means is that for the foreseeable future inflation is something to be aware of, and to manage, but not to run from. In that environment, if you strategically diversify your stock holdings around the globe and hold bonds with relatively short maturities you’ll probably do just fine.

*Please note that this is not a forecast but rather a look at the range of outcomes I believe are reasonable.