Q: I’m worried markets will turn more volatile next year. Should I sell?

A: It’s important to accept that market selloffs are a regular occurrence.

Let’s acknowledge that no one likes seeing markets fall and their portfolio balances decline. But the reality is that market selloffs are a normal part of being an investor. In fact, the stock market as a whole declines roughly 3 out of every 10 years…..and yet in the long run, the stock market has created fantastic wealth for generations of investors. The key is to accept that volatility is likely to occur at some point each and every year, and that as long as you don’t need to sell during those periods, you shouldn’t let these normal occurrences cause you undue stress.

Think of it like this: People living in Toronto might not like cold, snowy days. But come January, when the weather is cold or snowy, they aren’t surprised by the weather. And, those folks also know that the winter weather will pass, and that they’ll eventually enjoy a beautiful summer day. It’s the same way with markets; selloffs are part of the deal, but a century of experience shows us that markets eventually stabilize and resume their long run upward trend.

Annual Market Performance (grey bar) and Intra-Year Decline (red dot)

Q: Does it make sense to buy 2024’s winners at the start of 2025?

A: Maybe. Maybe not.

The reality is that there is little evidence that past performance is a predictor of future returns. In fact, the best (and worst) performers often rotate from year-to-year and even quarter-to-quarter. By definition, diversified portfolios mean that you won’t be concentrated in the best performing asset class in a given time period. But the corollary to that is you won’t be concentrated in the worst performing asset class in a given period.

Quarterly Asset Class Performance from Best to Worst

Source: Ycharts, Economic Update, Released October 2024.

Q: What’s the downside of concentration in tech stocks?

A: The downside is possibly not retiring (or going back to work if you’re already retired.)

It can be tempting to invest in what’s done well lately, but there are numerous examples of times that wouldn’t have worked out. One that happened to involve tech stocks was the 1990s dotcom boom, which featured soaring values of many early internet companies. Of course, when that bubble burst in the early 2000s, the S&P 500 went on to post a full decade of negative returns (tech stocks themselves did even worse.)

Ask yourself this: What would a full decade of negative returns do to your retirement plans?

The Lost Decade: S&P 500 Performance (2000-2009)

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, A Tale of Two Decades: Lessons for Long-Term Investors, February 2020.

The interesting thing about that decade is that even as the S&P and Nasdaq were stagnating, many other asset classes posted solid (and at times spectacular) returns. The end result was that diversified investors didn’t have nearly as much fun during the 1990s….but they also didn’t suffer nearly as bad a hangover when the clock struck midnight.

Performance of Various Classes (2000-2009)

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, A Tale of Two Decades: Lessons for Long-Term Investors, February 2020.

Q: Should I try and time the market?

A: Only if your timing is perfect.

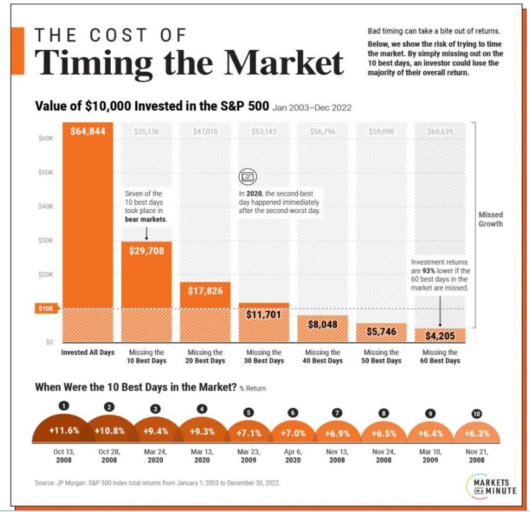

The reality is that a huge percentage of market returns are generated during a small subset of trading days, which means that if those are the days you aren’t invested, your returns drop sharply. The chart below shows that missing just 10 days over a two-decade period cuts returns in half. Missing the best 60 days cuts wealth by more than 90%!

Importantly, look at when the 10 best days occurred…they were all during the Great Financial Crisis or COVID, which are the periods market timers were probably most likely to be out of the market!

FYI: we chose the graphic below because it also highlights when the best days occurred, but the story remains the same when we run the numbers thru 2024.

Growth of $10,000 in the S&P 500

Source: VettaFi, 10 Best Days – A Meme For Every Bull Market, September 2023.

Q: Warren Buffet is selling stocks. Should you follow his lead?

A: Not unless your account is similar in size to his.

The graphic below shows a sampling of recent headlines around the famous ‘Oracle of Omaha’s’ recent stock sales. But, before you follow Buffett’s lead, there are a couple things you may want to consider. The first, and most important, is that Buffett himself has repeatedly stated that he can not time markets and does not know where stock prices are headed.

The second important consideration is that your opportunity set as an investor differs greatly from Buffett’s. The Oracle himself has alluded to this over the years, stating that he doesn’t expect his future performance to be as good as in the past, simply because his portfolio has gotten so big. Buffett’s size means that he needs to focus on a small subset of companies, some of whose prices might currently be elevated.

However, as an individual investor, you have a broader menu to choose from. In addition to large U.S. stocks, you can also consider smaller U.S. companies and the universe of global offerings. Many of these companies have stock prices that remain fairly valued.

Recent News Headlines about Warren Buffett

- Berkshire Hathaway’s cash fortress tops $300 billion as Buffett sells more stock, freezes buybacks

- Warren Buffett is fearful – or just waiting. Why the Oracle of Omaha is sitting on his cash hoard

- Why you might want to copy Warren Buffett and stash the cash

- Warren Buffett’s $166 billion warning to Wall Street has hit a fever pitch and the financial world can’t afford to ignore it

Q: How have markets and investors done over time?

A: Markets have done just fine…but investors are another story.

There was a famous study that looked at how various asset classes and portfolio allocations did during the first two decades of the 21st Century, and then compared that to how the average investor had done. During that time frame some asset classes (such as REITs, Emerging Market Stocks, and Small Company Stocks) did better than others. Over different time horizons, the best or worst performing asset classes are likely to fluctuate.

But the important takeaway is that the average investor did far worse than almost any asset class. So yes, overweighting a particular ‘winner’ can help returns. But the real key is to avoid the critical mistakes average investors make. That means not giving in to the temptation to pile into recent winners, or to become too aggressive in bull markets or too conservative in bear markets.

Asset Class and Average Investor Returns (1st Two Decades of 21st Century)